INVISIBLE STRESS: symptoms of chronic stress and what to do

We can define stress as the response our body produces in the face of an internal or external demand. When this response is sustained over time, symptoms of chronic stress may appear that affect the body, emotions, behavior, and mind. In other words, when the organism detects that it must adjust to cope with a situation, it sets physical and mental mechanisms in motion to respond. [1]

That said, stress is not necessarily negative. In the short term it can be useful and protective. However, the problem appears when the response is activated with too much intensity, too often, or for too long, without recovery.

Is this happening to you?

If you recognize yourself while reading this, and you’ve noticed symptoms of chronic stress, further down you’ll find an exercise and concrete steps. 👉 Go to “Steps to lower stress”

Example of an external demand

For example, if we perceive that we are in danger and believe we must run, the body gets ready. Alarm circuits in the brain are activated, the sympathetic nervous system kicks in, the pupils dilate, the muscles tense, breathing and pulse increase, energy is released to act, and we feel fear, which drives us to flee. If the situation continues, more sustained hormonal responses are also activated, such as the release of cortisol by the adrenal glands. [2]

Example of an internal demand

Likewise, if we do strength training, even if we don’t “think” we are in danger, the body registers the load: mechanical tension, metabolic changes, and microdamage to muscle fibers. Faced with this demand, it activates mechanisms to adapt: it mobilizes energy, adjusts the nervous system, and sets repair processes in motion (controlled inflammation and subsequent tissue synthesis). This is also stress: a biological response to maintain function and improve future tolerance (hormesis). [3]

Importantly, perception is only the tip of the iceberg: many internal demands (inflammation, lack of sleep, hypoglycemia, overload, …) are already adding physiological load before you even notice, so symptoms of chronic stress can build up even when you don’t feel “stressed.”

Allostatic load and chronic stress symptoms: the “accumulated cost” of stress

Once you understand what stress is, it’s useful to introduce the concept of allostatic load. Allostatic load is the cumulative wear and tear the body experiences when the stress response is activated repeatedly or persistently and recovery is not sufficient. In practice, this wear and tear is often noticed as stress symptoms (physical, emotional, behavioral, or cognitive). [4]

Which systems sustain it?

The most common allostatic responses involve two major pathways:

- Sympathetic nervous system (fast response): activates the state of alertness and promotes the release of adrenaline and noradrenaline (catecholamines). This increases pulse, breathing, muscle tension, and energy availability.

- HPA axis (more sustained response): the hypothalamus activates the pituitary gland, and this in turn activates the adrenal glands, which release cortisol.

How stress becomes chronic

Normally, after the demand passes, the body “switches off” these systems and returns to its baseline. The problem arises when this inactivation is inefficient, or when demands accumulate without rest: there is an overexposure to stress mediators (such as cortisol and catecholamines), and over time allostatic load increases. We call this situation chronic stress. [4]

If you find it hard to disconnect, it can be worked on

In consultation we’ll identify maintaining factors (sleep, rumination, pain, diet, overload, …) and figure out where to start.

👉 Book an appointment (Psychology / PNIE / Dietetics)

Photo of Protective and Damaging Effects of Stress Mediators (1998)[4]

Typical patterns of chronic stress (graphs)

In the first graph we see a “healthy” stress response: there is a period of activation in response to the demand and then a period of relaxation/recovery (return to baseline). The other graphs show typical patterns of chronic stress, when activation repeats too much or doesn’t switch off properly:

- “Repeated hits”: too many very frequent stress peaks, without enough time to recover.

- “Lack of adaptation”: repeated stress peaks without adaptation; the body responds as if each exposure were new.

- “Prolonged response”: an elevated stress response sustained for too long, with slow “inactivation.”

- “Inadequate response”: a different pattern in which the activation response is low or mismatched when it would be expected (described in some cases of sustained stress and chronic pain).

To give examples of how allostatic load accumulates, it’s worth remembering that it’s not only “external” stressors that count. Anticipation and worry also add to the total load. Even without a real threat, anticipatory anxiety can keep stress mediators (such as cortisol and adrenaline) activated. Habits and context matter too: tobacco and alcohol use, dietary choices, and an exercise dose that’s poorly adjusted (too much or too little) can all contribute.

In short: the more stressors you pile up and the less you recover, the greater the allostatic load you carry. This accumulation often shows up as symptoms of chronic stress or as lower tolerance to everyday stressors. With a higher load, it becomes harder to cope with new demands—stress tolerance drops and vulnerability increases.

Stress tolerance and vulnerability: why it affects some people more

Stress tolerance is, essentially, your margin: the ability to activate in response to a demand and return to your baseline relatively quickly. Vulnerability appears when that margin shrinks. It doesn’t mean “being weak”: it means your system is already loaded and has less space to absorb new demands.[5]

Think of it like a glass: if your glass is half full due to lack of sleep, hypoglycemia, pain, inflammation, constant worries, or too much caffeine, any extra drop overflows it. This “half-full glass” is often accumulated allostatic load. That’s why two people can experience the same stimulus (an intense week, a conflict, or a bad night) and react very differently.

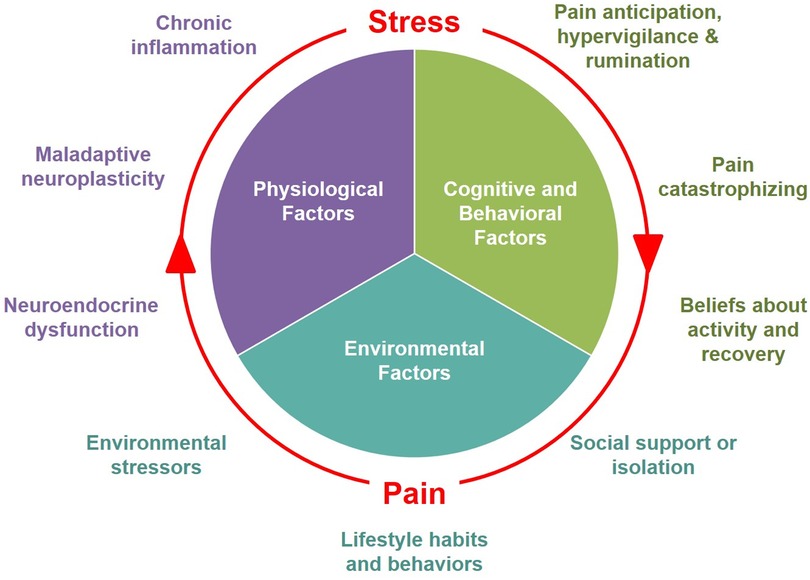

In the following figure you can see some of the interactions between mental stress, physical stress (from pain), and how the allostatic load loop is maintained:

Photo of The mutually reinforcing dynamics between pain and stress [6]

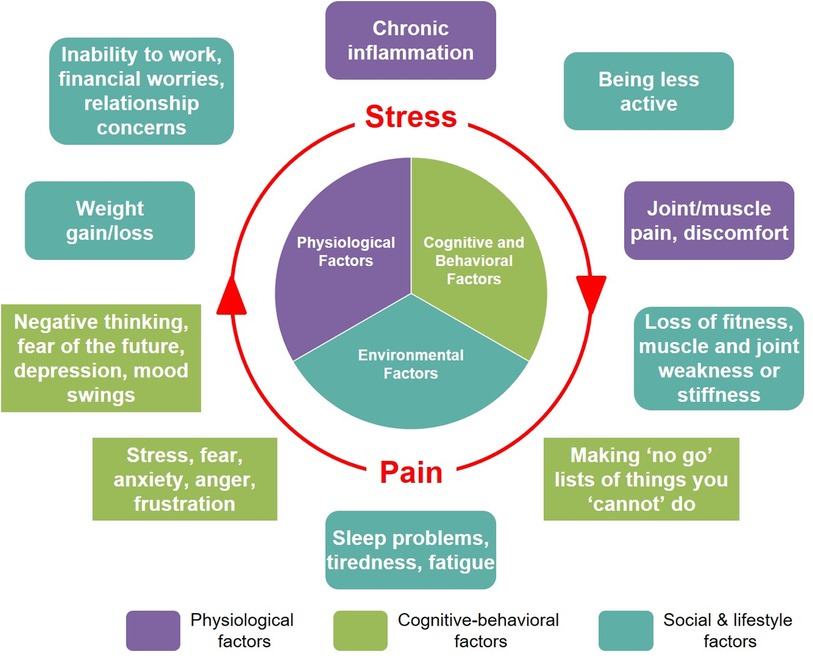

And here you can see how many factors may be involved behind this maintenance. This is just one example: there can be many more.

Photo of The mutually reinforcing dynamics between pain and stress [6]

Since many factors can be involved at once, it’s important to act from a position of awareness. There may be something in your life that is clearly stressful, but there may also be other elements contributing that you’re not detecting. Often, it’s also easier to intervene on these “secondary” factors than on the big problem you’re going through right now.

Exercise: reduce stress symptoms and identify your stress load

If you suspect what’s happening fits chronic stress symptoms, this exercise will help you identify what is adding load and what is maintaining it.

- Identify stressors: what or who causes you stress?

- Define the origin: in which situations does your stress appear?

- Explore your beliefs: where is the “danger”? what negative consequences do you fear?

- Detect maintaining factors: what do you think keeps your stress going (habits, thoughts, conflicts, lack of rest, etc.)

Video: two tools to work on your stressors

In the following video from my talk “Taming stress” you can see two very useful tools to work with the stressors you detected in the previous exercise.

Below I leave you clear action steps to address stress depending on which type of response predominates in your life right now.

Symptoms of chronic stress: how invisible stress shows up

Stress response of physiological origin

Symptoms you may experience

- Cardiovascular: rapid palpitations, high blood pressure, chest pain, chest tightness.

- Respiratory: difficulty breathing, feeling short of breath.

- Digestive: diarrhea, constipation, nausea, stomach knot, heartburn, pain in the pit of the stomach, bloating, gas, intestinal spasms.

- Neurological: headache, dizziness, vertigo, tingling, numbness, tremors, hypersensitivity to light or sound.

- Sensory: ringing (tinnitus), temporary blurred vision.

- Musculoskeletal: muscle tension, neck tension, muscle spasms, bruxism, jaw pain, jaw clicking.

- Skin and appendages: dermatitis, acne flare-ups, hair loss, hives, itchy welts, dandruff, dryness and flaking.

- Immune: cold sores, slow healing, tendency to get sick, worsening allergies.

- Hormonal and reproductive: decreased sex drive, changes in the menstrual cycle, absence of menstruation.

- Sleep: insomnia, frequent awakenings, non-restorative sleep, nightmares.

- Mouth and throat: dry mouth, feeling of a lump in the throat, difficulty swallowing, throat clearing or nervous cough.

- Urinary: frequent urination, urinary urgency, getting up to urinate at night.

- General symptoms: sweating, chills, facial flushing, persistent fatigue, changes in appetite, weight changes.

Some illnesses and conditions to rule out

If symptoms are intense, frequent, or persistent, it’s advisable to rule out medical causes (especially if they are not diagnosed or well controlled), such as: diabetes, hypoglycemia, hypertension, Cushing syndrome, fibromyalgia, hyperthyroidism, hypothyroidism, anemia, B12 or iron deficiency, asthma, gastritis, ulcer, benign paroxysmal positional vertigo, vestibular neuritis or labyrinthitis, atopic dermatitis, psoriasis, urticaria, seborrheic dermatitis, gastroesophageal reflux, irritable bowel syndrome, migraine, sleep apnea, menopause, heart rhythm disorders (arrhythmias), lactose intolerance, gluten sensitivity, celiac disease, small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO). [7]

Some substances and medications that can cause or worsen these symptoms

Substances: coffee, tea, caffeinated drinks, energy drinks, guarana, tobacco, vapes/nicotine, alcohol, amphetamines, cocaine.

Medications (depending on case/dose): corticosteroids, asthma inhalers (bronchodilators), antidepressants, levothyroxine.

Abrupt withdrawal: withdrawal from medications or drugs (withdrawal syndrome).

Steps to follow:

- Go to the doctor to rule out physical causes, review medication, and get a diagnosis.

- Accept what is happening to you: it’s the first step to start improving.

- If there is an underlying illness, follow treatment and keep it under control; otherwise, symptoms may recur.

- Improve your lifestyle: take care of rest and sleep, nutrition, and do physical activity. If you do, your stress tolerance and symptoms will probably improve. If in doubt, consult your doctor.

- Reduce avoidable stressors whenever possible.

Stress response of emotional origin

What you may feel: irritability, constant irritation, nervousness, anxiety, restlessness, distress, unease, feeling on alert, hypervigilance, overwhelm, fear, feeling threatened, impatience, frustration, anger/outbursts, hostility or susceptibility, hypersensitivity to criticism, constant hurry or urgency, sadness, easy crying, discouragement, guilt, shame, insecurity, feeling of failure, helplessness or defenselessness, feeling of loss of control, emotional exhaustion, apathy or lack of motivation, loss of interest or enjoyment, feeling empty, emotional numbness, feeling disconnected or unreal, loneliness, detachment or cynicism, hopelessness.

Steps to follow:

- Identify which emotion you are feeling and name it.

- Notice which situations or people trigger it (and what you’re telling yourself inside).

- Observe how you’re managing it now (avoiding, exploding, staying silent, compensating, etc.).

- Choose concrete emotional regulation tools (breathing, pause, writing, boundaries, communication, etc.).

- Apply techniques to reduce intensity and frequency (and repeat: consistency is the key).

- Express what you feel appropriately (without swallowing everything or exploding).

- If you need it or have doubts, seek professional support: doctor, psychologist, psychiatrist, or therapist.

Stress response of behavioral origin

What we do: avoid, procrastinate, never stop and overload ourselves, constantly control and check, act impulsively, argue or overreact, isolate ourselves, consume to “calm down” (alcohol, nicotine, caffeine, supplements, herbs, or other substances), fall into compulsive behaviors (eating, social media, gambling, sex), neglect self-care, change how we communicate (silence or explode), punish ourselves with excessive self-demands.

Steps to follow:

- Spot the pattern: if you always end up avoiding, running away, or “anesthetizing yourself,” that’s the behavior that needs to change.

- Identify triggers: which situations, people, or thoughts activate avoidance, impulsivity, or compulsiveness.

- Choose one concrete alternative: define what you’ll do instead of that pattern (e.g., “when I get stuck, I’ll do 10 minutes and stop”).

- Gradual exposure: approach what you avoid in small, repeated steps (not all at once).

- Set healthy limits in your personal relationships: schedules, loads, communication, learn to say “no”.

- Seek professional support: doctor, psychologist, psychiatrist, or therapist.

Stress response of cognitive origin

What we think: worrying excessively, going over it again and again (rumination), anticipating the worst (catastrophizing), imagining negative scenarios, feeling that “everything is too much,” going blank or freezing, difficulty concentrating, memory lapses, indecision, need for certainty and control, self-demand (“I should be able to handle everything”), harsh self-criticism, comparing ourselves to others, interpreting neutral signals as a threat, overgeneralizing (“if I fail here, I fail at everything”), all-or-nothing thinking (“either perfect or a disaster”), mind reading (“they surely think…”), personalizing (“it’s my fault”), filtering the negative (I only see what’s going wrong), intrusive thoughts, feeling of constant urgency.

Steps to follow: [8]

- Identify stressful thoughts (what you’re telling yourself).

- Test their truth: what facts support it and what facts contradict it?

- Test probability: what is most likely, not what is most feared?

- Find alternative thoughts: more realistic and useful.

- Remind yourself at key moments (note on your phone/planner) so you don’t return to the automatic thought.

- If you need it or have doubts, seek professional support: doctor, psychologist, psychiatrist, or therapist.

Tips to reduce chronic stress symptoms and improve your stress tolerance

These habits help reduce chronic stress symptoms and restore your tolerance margin.

- Prioritize sleep: stable schedule, natural light in the morning, fewer screens at night. [9]

- Do regular physical activity, adapted to your physical condition. [10]

- Practice slow, deep breathing (5–10 minutes a day: slow and nasal if you can).

- Calming practices: meditation, mindfulness, or guided relaxation (whatever you can stick with). [11]

- Reduce stimulants if you’re activated: coffee, tea, cocoa, energy drinks, guarana, and “pre-workouts”.

- Review substances and medication if you notice they trigger symptoms (don’t change anything without consulting).

- Stable nutrition: enough calories and protein, regular meals, good hydration.

- Check for deficiencies if symptoms persist (iron, B12, vitamin D, magnesium depending on the case) and supplement if needed (consult a professional).

- Include omega-3 in your diet (oily fish 3 times per week or supplementation).

- Mental offload: write down what worries you (list of “what depends on me / what doesn’t”).

- Intentionally shift attention: social contact, nature, hands-on tasks, music, hobbies.

- Stimulate the parasympathetic system: slow breathing, brief cold water if it works for you, humming/singing, muscle relaxation, gentle walks.

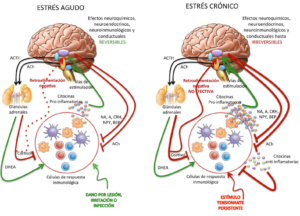

One last warning: don’t ignore symptoms of chronic stress. When it persists over time, it can have important consequences. Below I leave you a graph showing how chronic stress can alter the immune system response and keep neuroendocrine and neuroimmune pathways associated with sustained inflammation activated.

Photo of Temas Selectos en Neurobiología Molecular e Integrativa (2017) [12]

Do you want help applying this to your case?

If you’ve had stress symptoms for a while and can’t improve on your own, asking for help can speed up change a lot.

👉 Request an appointment

REFERENCES

- Psychological stress and disease. (2007) https://www.researchgate.net/publication/5918645_Psychological_stress_and_disease_JAMA_298_1685-1687

- Physiology and neurobiology of stress and adaptation: Central role of the brain.(2007) https://journals.physiology.org/doi/full/10.1152/physrev.00041.2006?

- Hormesis and Exercise: How the Cell Copes with Oxidative Stress. (2008) https://tf.hu/wp-content/uploads/2009/08/Rad%C3%A1k-Zsolt-NTK-60.pdf

- Protective and Damaging Effects of Stress Mediators (1998) https://www.psychiatry.wisc.edu/courses/Nitschke/seminar/mcewen_njm_1998.pdf

- Heart Rate Variability and Cardiac Vagal Tone in Psychophysiological Research – Recommendations for Experiment Planning, Data Analysis, and Data Reporting (2017). https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/psychology/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00213/full

- The mutually reinforcing dynamics between pain and stress: mechanisms, impacts and management strategies (2024) https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/pain-research/articles/10.3389/fpain.2024.1445280/full

- Biobehavioral approach to distinguishing panic symptoms from medical illness (2024) https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/psychiatry/articles/10.3389/fpsyt.2024.1296569/full

- Cognitive behavioral therapy for anxiety and related disorders: A meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled trials. (2018) https://europepmc.org/article/MED/29451967?

- The effect of acute sleep deprivation on cortisol level: a systematic review and meta-analysis (2024) https://www.jstage.jst.go.jp/article/endocrj/71/8/71_EJ23-0714/_article/-char/en?

- Physical activity and cortisol regulation: A meta-analysis (2023) https://midus.wisc.edu/findings/pdfs/2669.pdf

- Meditation programs for psychological stress and well-being: systematic review and meta-analysis. (2014) https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamainternalmedicine/fullarticle/1809754?

- Temas Selectos en Neurobiología Molecular e Integrativa (2017) https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Eric_Murillo-Rodriguez/publication/320630502_Temas_Selectos_en_Neurobiologia_Molecular_e_Integrativa/links/59f3158faca272607e270297/Temas-Selectos-en-Neurobiologia-Molecular-e-Integrativa.pdf

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!